The task of recognizing textual entailment, also known as natural language inference, consists of determining whether a piece of text (a premise), can be implied or contradicted (or neither) by another piece of text (the hypothesis). While this problem is often considered an important test for the reasoning skills of machine learning (ML) systems and has been studied in depth for plain text inputs, much less effort has been put into applying such models to structured data, such as websites, tables, databases, etc. Yet, recognizing textual entailment is especially relevant whenever the contents of a table need to be accurately summarized and presented to a user, and is essential for high fidelity question answering systems and virtual assistants.

In “Understanding tables with intermediate pre-training“, published in Findings of EMNLP 2020, we introduce the first pre-training tasks customized for table parsing, enabling models to learn better, faster and from less data. We build upon our earlier TAPAS model, which was an extension of the BERT bi-directional Transformer model with special embeddings to find answers in tables. Applying our new pre-training objectives to TAPAS yields a new state of the art on multiple datasets involving tables. On TabFact, for example, it reduces the gap between model and human performance by ~50%. We also systematically benchmark methods of selecting relevant input for higher efficiency, achieving 4x gains in speed and memory, while retaining 92% of the results. All the models for different tasks and sizes are released on GitHub repo, where you can try them out yourself in a colab Notebook.

Textual Entailment

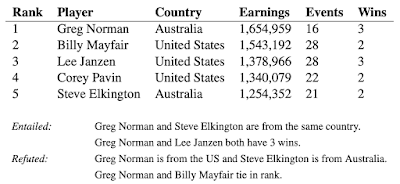

The task of textual entailment is more challenging when applied to tabular data than plain text. Consider, for example, a table from Wikipedia with some sentences derived from its associated table content. Assessing if the content of the table entails or contradicts the sentence may require looking over multiple columns and rows, and possibly performing simple numeric computations, like averaging, summing, differencing, etc.

|

| A table together with some statements from TabFact. The content of the table can be used to support or contradict the statements. |

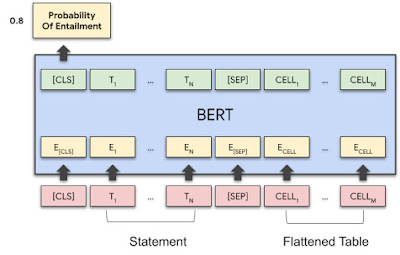

Following the methods used by TAPAS, we encode the content of a statement and a table together, pass them through a Transformer model, and obtain a single number with the probability that the statement is entailed or refuted by the table.

|

| The TAPAS model architecture uses a BERT model to encode the statement and the flattened table, read row by row. Special embeddings are used to encode the table structure. The vector output of the first token is used to predict the probability of entailment. |

Because the only information in the training examples is a binary value (i.e., “correct” or “incorrect”), training a model to understand whether a statement is entailed or not is challenging and highlights the difficulty in achieving generalization in deep learning, especially when the provided training signal is scarce. Seeing isolated entailed or refuted examples, a model can easily pick-up on spurious patterns in the data to make a prediction, for example the presence of the word “tie” in “Greg Norman and Billy Mayfair tie in rank”, instead of truly comparing their ranks, which is what is needed to successfully apply the model beyond the original training data.

Pre-training Tasks

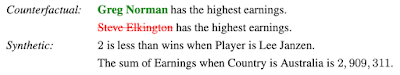

Pre-training tasks can be used to “warm-up” models by providing them with large amounts of readily available unlabeled data. However, pre-training typically includes primarily plain text and not tabular data. In fact, TAPAS was originally pre-trained using a simple masked language modelling objective that was not designed for tabular data applications. In order to improve the model performance on tabular data, we introduce two novel pretraining binary-classification tasks called counterfactual and synthetic, which can be applied as a second stage of pre-training (often called intermediate pre-training).

In the counterfactual task, we source sentences from Wikipedia that mention an entity (person, place or thing) that also appears in a given table. Then, 50% of the time, we modify the statement by swapping the entity for another alternative. To make sure the statement is realistic, we choose a replacement among the entities in the same column in the table. The model is trained to recognize whether the statement was modified or not. This pre-training task includes millions of such examples, and although the reasoning about them is not complex, they typically will still sound natural.

For the synthetic task, we follow a method similar to semantic parsing in which we generate statements using a simple set of grammar rules that require the model to understand basic mathematical operations, such as sums and averages (e.g., “the sum of earnings”), or to understand how to filter the elements in the table using some condition (e.g.,”the country is Australia”). Although these statements are artificial, they help improve the numerical and logical reasoning skills of the model.

Results

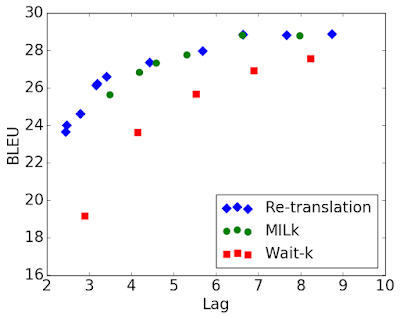

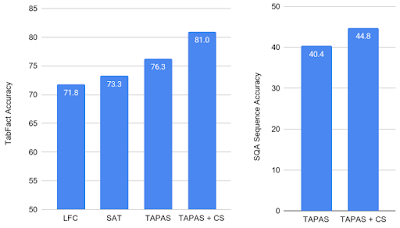

We evaluate the success of the counterfactual and synthetic pre-training objectives on the TabFact dataset by comparing to the baseline TAPAS model and to two prior models that have exhibited success in the textual entailment domain, LogicalFactChecker (LFC) and Structure Aware Transformer (SAT). The baseline TAPAS model exhibits improved performance relative to LFC and SAT, but the pre-trained model (TAPAS+CS) performs significantly better, achieving a new state of the art.

We also apply TAPAS+CS to question answering tasks on the SQA dataset, which requires that the model find answers from the content of tables in a dialog setting. The inclusion of CS objectives improves the previous best performance by more than 4 points, demonstrating that this approach also generalizes performance beyond just textual entailment.

|

| Results on TabFact (left) and SQA (right). Using the synthetic and counterfactual datasets, we achieve new state-of-the-art results in both tasks by a large margin. |

Data and Compute Efficiency

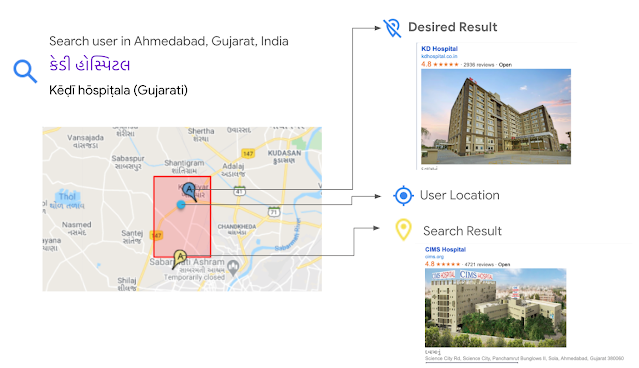

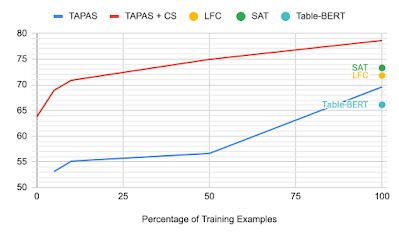

Another aspect of the counterfactual and synthetic pre-training tasks is that since the models are already tuned for binary classification, they can be applied without any fine-tuning to TabFact. We explore what happens to each of the models when trained only on a subset (or even none) of the data. Without looking at a single example, the TAPAS+CS model is competitive with a strong baseline Table-Bert, and when only 10% of the data are included, the results are comparable to the previous state-of-the-art.

|

| Dev accuracy on TabFact relative to the fraction of the training data used. |

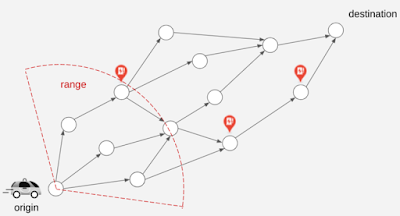

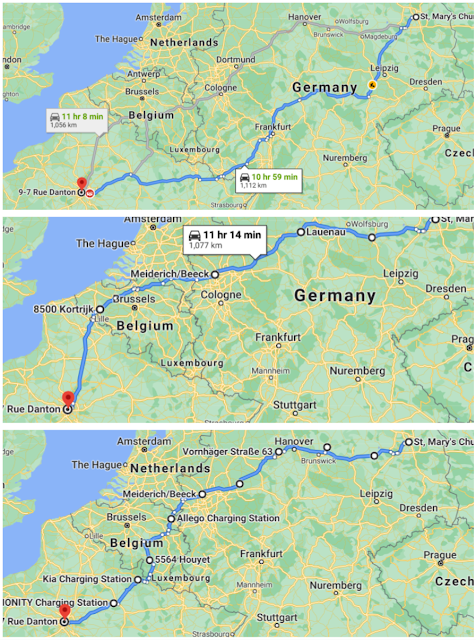

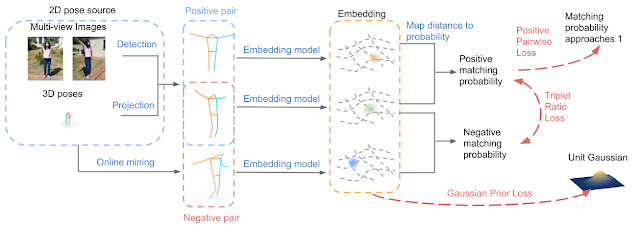

A general concern when trying to use large models such as this to operate on tables, is that their high computational requirements makes it difficult for them to parse very large tables. To address this, we investigate whether one can heuristically select subsets of the input to pass through the model in order to optimize its computational efficiency.

We conducted a systematic study of different approaches to filter the input and discovered that simple methods that select for word overlap between a full column and the subject statement give the best results. By dynamically selecting which tokens of the input to include, we can use fewer resources or work on larger inputs at the same cost. The challenge is doing so without losing important information and hurting accuracy.

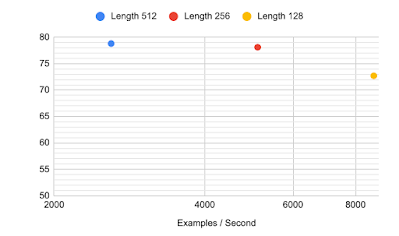

For instance, the models discussed above all use sequences of 512 tokens, which is around the normal limit for a transformer model (although recent efficiency methods like the Reformer or Performer are proving effective in scaling the input size). The column selection methods we propose here can allow for faster training while still achieving high accuracy on TabFact. For 256 input tokens we get a very small drop in accuracy, but the model can now be pre-trained, fine-tuned and make predictions up to two times faster. With 128 tokens the model still outperforms the previous state-of-the-art model, with an even more significant speed-up — 4x faster across the board.

|

| Accuracy on TabFact using different sequence lengths, by shortening the input with our column selection method. |

Using both the column selection method we proposed and the novel pre-training tasks, we can create table parsing models that need fewer data and less compute power to obtain better results.

We have made available the new models and pre-training techniques at our GitHub repo, where you can try it out yourself in colab. In order to make this approach more accessible, we also shared models of varying sizes all the way down to “tiny”. It is our hope that these results will help spur development of table reasoning among the broader research community.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out by Julian Martin Eisenschlos, Syrine Krichene and Thomas Müller from our Language Team in Zürich. We would like to thank Jordan Boyd-Graber, Yasemin Altun, Emily Pitler, Benjamin Boerschinger, Srini Narayanan, Slav Petrov, William Cohen and Jonathan Herzig for their useful comments and suggestions.